The cash flowed—and so did the drinks—at taverns across the Caribbean during the golden age of piracy. But these watering holes weren’t just for getting drunk.

When pirates weren’t marauding on the high seas between the 1650s and 1730s—the so-called golden age of piracy—they sought haven in Caribbean ports to restock their goods, fix their ships, and hide from authorities. During these downtimes, they often spent their time in taverns.

Any Caribbean port worth its salt offered a bevy of drinking establishments where locals and travellers—including pirates—could come together and enjoy a hearty drink. Without doubt, pirates had a propensity for drunkenness. They were frequently described as drunk and disorderly, but it wasn’t all about villainy and debauchery. Wheeling and dealing was the name of the game.

Choices, choices

Back then, pirates had a choice of two types of drinking establishments: public houses (or pubs) and taverns. A public house was, quite literally, a private house that was made public. At a time when brewing ale and beer was poorly regulated and untaxed, many people saved money by brewing their own. Anyone with an excess of ale might open their house to passers-by, including pirates—those wanting to keep a low profile would be especially interested.

Taverns, on the other hand, were spaces built for the sole purpose of selling drinks, serving meals, and providing entertainment. A good tavern would have a sitting area, a bar, a dance floor, and even a stable to look after a customer’s horse. Sale notices, reward posters for enslaved individuals who had escaped, and news of trials and hangings covered the walls. Local prostitutes worked the crowd. Taverns were open regular hours and sold other drinks besides ale, notably wine, rum, and whiskey. They often had upstairs rooms for visitors to overnight.

The art of deal-making

Despite their rowdy reputations, taverns often served as centres for community activities. For one, they functioned as informal places for sharing information and intelligence. Here, news about the latest political scandal or treaty negotiation could circulate widely. In Barbados during the 17th century, for example, the assembly regularly met at a tavern instead of a dedicated meetinghouse. Secondly, taverns often operated as a casual place of commercial negotiation.

Pirates also used these public spaces to their advantage. In between swills, they interacted with a variety of individuals, recruiting sailors, promoting mutiny on merchant vessels, and learning about the trade routes of various merchant ships.

Pirates also made business deals with society’s rich upper-class merchants and political figures, who didn’t dare be seen with them in traditional commercial sites. One visitor to Jamaica, John Taylor, remarked in 1683 that the island’s inhabitants possessed a great amount of wealth and myriad modes of entertainment because of the pirates and privateers—pirates operating with official permission from the British crown to protect their interests from the Spanish– who frequented the taverns and brothels there.

Fuelling the consumer revolution

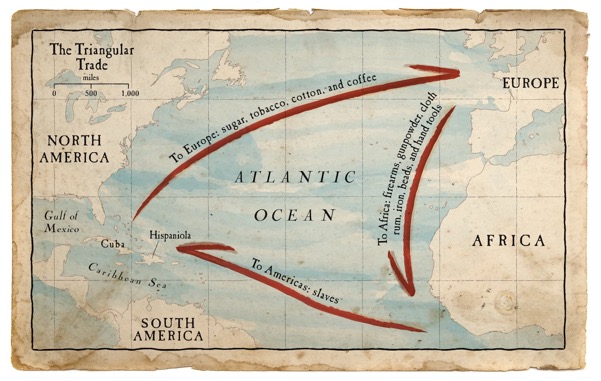

During that time, Europe, led by England, developed policies, created trade routes, enslaved Africans, and protected markets connected to their colonies in America. This triangular trade network, which provided Europe with raw materials like cotton, tobacco, and indigo from the colonies to turn into finished goods and relied on the work of enslaved individuals, fueled a consumer revolution—a huge demand among commoners and gentry alike to possess material goods that suddenly were more affordable. Societies used to scarcity suddenly were bombarded by frenzied consumption.

The taverns became hubs of economic activity in this new type of economy. Merchants, tavern keepers, inhabitants, and pirates were all involved in the business of trading fashionable and luxury items, including tea, furniture, clothing, and spices.

Fencing loot

Pirates also traded in expensive ill-gotten loot. It’s no secret that in the course of their jobs, they plundered valuable items from their victims. But what use did they have with Chinese porcelain, English and Dutch blue-on-white tin-glazed earthenware, and fancy German Westerwald ware? Tavern owners readily took these costly items off their hands (no doubt at a fraction of the original price), thereby supplementing their own collections. The pirates, in turn, may have their profits in the same establishment.

Pirates also hawked their goods to unscrupulous dealers, who would later sell them through legitimate channels. In this way, average people collected a wide variety of cultural material that they might not otherwise have had access to or been able to afford. Of course, this did little to help the rightful owners who had no hope of regaining their treasures.

Drink As The Great Equaliser

Women played an important role in tavern life. They were quite often licensed drink sellers throughout the Caribbean. And many women were cited for operating unlicensed or disorderly houses on the islands, such as Martha Harris who, in 1655, was accused of selling liquor illegally from her home. Harris was so invested in illicit alcohol sales that she declared if the authorities seized what she had, she would just get more and sell it. Additionally, in many of the port towns that pirates frequented, women were quite often tavern patrons or workers.

Cash flow

By virtue of their business practices, pirates dealt in large amounts of cash. In 1683, a visitor to Port Royal, Jamaica, named Francis Hanson was astonished to find that, unlike in other locations, where accounts were kept in commodities such as sugar or tobacco, there was so much cash available in Jamaica that it rivaled the city of London.

According to 18th-century buccaneer Alexandre Exquemelin, taverns and brothels easily “got the greatest part” when it came to pirates’ booty. One piratical venture, for example, might allow a man to squander in a month 1,000 pieces of eight, a form of Spanish currency that became the world’s first global currency. Pirates were even known to drop two to three thousand pieces of eight in a single night, which was more than some local laborers would earn in a year.

The tavern keeper’s woes

As for the tavern keepers, income was income no matter what form it took, prompting them to freely supply pirates with their drinks of choice. No wonder Port Royal—one of the largest pirate havens at the time—boasted over 100 taverns by 1680.

Sometimes, this economic model led to trouble for the tavern keepers. In 1721, Port Royal locals accused a tavern keeper named John Dunks of supplying a pirate with men and provisions and allowing another pirate to escape persecution by springing him from jail. John Perrie, a tavern owner in Antigua, was accused of trading with pirates in his tavern at St. John’s and harbouring pirates from the law.

The importance of taverns

Taverns offered Atlantic world inhabitants, including pirates, a location in which they might conduct business, share knowledge, and create economic and social networks without fear of government interference.

The islands of the Atlantic world were particularly well suited to host such exchanges, as inhabitants often relied on pirates and innovative merchants to provide necessary goods and services that were disrupted during incessant periods of international warfare.

Without taverns, pirates would have had a much more difficult time fencing their loot and refitting their ships. They also would have had no place to spend their ill-gotten money or enjoy their free time.