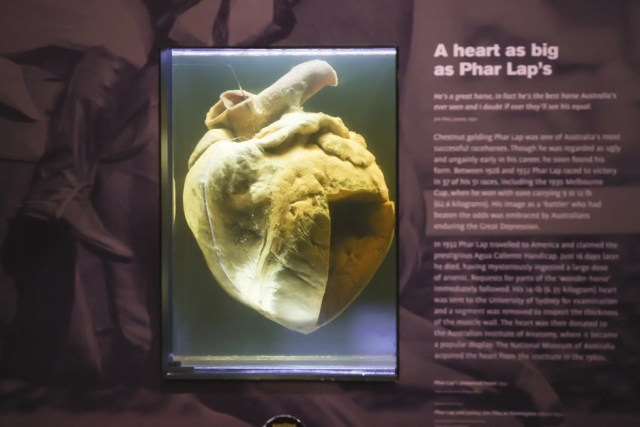

The heart of Phar Lap is the most visited item on display at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. CREDIT:ALEX ELLINGHAUSEN

As a child Kerry Negara was regaled by stories of Phar Lap almost straight from the horse’s mouth.

Her life-long obsession with Australia’s most famous thoroughbred was inspired by tales from an old family friend – the strapper and later trainer of “Big Red”, Tommy Woodcock.

Almost 90 years since the death of the 1930 Melbourne Cup winner at Menlo Park, California, the circumstances of the horse’s tragic end remain wrapped in suspicion, mythology, and confusion.

Phar Lap racing to win in 1930.CREDIT:ARCHIVES

“I grew up with the story of how Phar Lap died, and by whose hand,” she says. “Directly from Tommy himself, as told to my parents Thelma and Cliff [Hinchliffe]. It’s not a classic flawed ‘Tommy told me’ story but rather a true story that comes from an enduring lifetime of friendship.”

In recent years the smart money has been on a bacterial infection. But over the decades weight has also been placed on various theories that the horse was either deliberately or accidentally poisoned with arsenic, developed colic, or ate grass which had been freshly sprayed with weedkiller.

Negara, a researcher, filmmaker, and podcaster, remains convinced Phar Lap was killed by men linked to the mafia who were nervous about losing their fortunes in illegal bookmaking scams.

She is also hellbent on myth busting another part of the legend.

How Phar Lap Died

Her nine-part podcast Killing Phar Lap: A Forensic Investigation revisits a 40-year-old claim that Phar Lap’s heart – displayed at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra – is a fake.

The saying “a heart as big as Phar Lap” entered the Australian lexicon as a symbol of courage or victory against adversity not long after the 14-pound (6.35 kilogram) heart was removed by stable vet Bill Nielsen and with jockey Billy Elliot escorting it in a jar of formalin to the boat bound for Sydney.

The organ, more than 1.5 times the weight of an average thoroughbred racehorse heart, was sent to the University of Sydney, where it had been requested for examination by Dr Stewart McKay.

It was then acquired by and placed on display at the Australian Institute of Anatomy in July 1932. When the institute closed in 1984, the heart became part of the museum where it has continued to enthral a new generation of visitors.

The problem? The vet who removed the heart told his daughter, Mary McCann, that it is not Phar Lap’s heart at all.

McCann told journalist Peter Luck three decades ago that when she suggested visiting the heart on a trip to Canberra her father said, “Well that will be clever – it’s not Phar Lap’s heart. It’s a draft horse’s”, adding the original had been “cut to pieces in the first post-mortem”.

Luck, who died in 2017, remained convinced of McCann’s story and likened the heart to Australia’s “shroud of Turin”.

“In the end it doesn’t really matter whether this is Phar Lap’s heart or not,” he once said. “In the past 60 years several million Australians have seen it and it’s now well and truly an Aussie icon.”

Phar Lap wins the 1930 Melbourne Cup. CREDIT:THE AGE

But Negara finds the truth more interesting.

After several years of lobbying and presenting research – including the findings from several post-mortems – she succeeded in persuading the museum in 2017 to agree to subject samples of the heart to DNA testing.

In an email, museum director Mathew Trinca thanked her for the proposal and said while the directors were not willing to make the heart specimen available for testing they would offer other pieces of the heart, which had been preserved in fluid from the initial dissection of the organ in 1932.

“The NMA will proceed cautiously and take into account the best available scientific advice to ensure the fragile heart specimen is not damaged,” Trinca wrote.

“We hope you will understand that this approach enables the museum to balance its approach … in the national interest and care for the National Historical Collection.”

Negara was excited. But the process would move slowly and test her patience.

Researcher and podcaster Kerry Negara has a personal connection to Phar Lap and she believes the heart on display is not that of the racing icon.

A year later Trinca provided an update that the museum was still in the process of seeking to arrange testing and had received mixed professional advice on the likelihood of obtaining scientifically verifiable DNA from an 80-year-old heart.

“Mindful of the public interest involved in this case, we are moving to test Phar Lap’s heart pieces through an independent laboratory,” he wrote. “Please be assured that undertaking this research is a priority for us and we commit to have this completed by the end of February 2019.”

The months and years ticked by deadlines came and went and Negara lost faith, drafting an email to the museum’s director that she later thought the better of sending.

“The rate of ‘moving forward’ is so unbelievably slow, watching paint dry would be more engaging,” she wrote. “We’re now into our third year – and the fifth year since I presented my research. For me to be constantly on the cusp of believing the testing is imminent for over two years now is psychologically wearing and financially straining.”

By early 2020 the samples had made their way to the world’s leading equine genetic expert, Ludovic Orlando, a paleogeneticist and research director of the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse in France.

Negara had recommended the professor as the man most likely to get a result years earlier and, after consulting with Australian experts at the CSIRO, the museum had come to the same conclusion.

But with the laboratory shut down during the coronavirus pandemic, more than 18 months would pass before Professor Orlando excitedly notified the museum of his preliminary findings via email.

The laboratory had been given several samples which testing had revealed “extreme DNA degradation and limited DNA amounts”, he wrote to the museum’s head of curatorial centres Martha Sear on September 4 this year.

One sample, however, which had been matched against a sample of Phar Lap’s hair, did not carry the same mitochondrial genome and the nuclear genome did not match.

“What we can then say is while the hair, genetically, comes indeed from a chestnut thoroughbred (as expected), the tissues preserved in formaldehyde do not,” he wrote, adding it was more than likely a quarter horse.

Phar Lap is led back to the mounting yard at Flemington Racecourse after winning the Victoria Derby, Melbourne, November 1929.CREDIT:SMH ARCHIVES

Phar Lap is led back to the mounting yard at Flemington Racecourse after winning the Victoria Derby, Melbourne, November 1929.CREDIT:SMH ARCHIVES

Professor Orlando acknowledged the result would be a shock and volunteered to make himself available for an online meeting.

“It is extremely important that we keep this result strictly confidential at that stage and that we discuss the best strategy to disclose our findings,” he said.

Negara’s hopes soared and jaws at the museum dropped.

But it wasn’t the last twist in the saga. Days later it was confirmed the sample that had yielded the result was in fact a quarter-horse all along, and the sample test had been labelled as a “comparison army horse heart”.

Professor Orlando was devastated and seemingly embarrassed.

“I must express my surprise at that stage and can only regret the situation, given the efforts and resources invested in this study at my end,” he wrote. “Doubts about the authenticity of the jar were raised for the first time only today, and now I am realising that we may even have worked on some random horse specimen.”

Still, he recommended proceeding with the process and was hopeful results could be reached from tests of two other samples.

But in an email in September, Katherine McMahon, the museum’s assistant director of discovery and collections, called the process off.

“It is fascinating to think of what might have been possible had the heart specimen yielded usable data,” she wrote. “However, given the current state of even the most advanced techniques in this field, there seems little point in proceeding any further on the basis of your results.”

Both Negara and Professor Orlando were shocked at the response and pleaded in separate correspondence for the process to continue.

Trinca, spoke directly to the latter and says the pair both agreed to pause testing but vowed to revisit it when the techniques were further refined.

In a statement to The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, Professor Orlando said he could not comment on any specific analyses and results that his lab carried out because of a non-disclosure agreement with the museum.

“In ancient DNA research, we can never guarantee that there is sufficient amount of DNA preserved in a given sample to obtain positive results,” he said.

He said while he had been surprised the museum had included various kinds of samples and conceded he himself had made that suggestion during preliminary discussions with the museum.

Dr Mathew Trinca, director of the National Museum of Australia, with the Phar Lap’s heart exhibit at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra earlier this week.CREDIT:ALEX ELLINGHAUSEN

Dr Mathew Trinca, director of the National Museum of Australia, with the Phar Lap’s heart exhibit at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra earlier this week.CREDIT:ALEX ELLINGHAUSEN

“Given that our analyses are destructive, it is thus reasonable to not damage the other remains further until more advanced technologies may become available,” he said.

Negara is heartbroken at the decision and plans to fight it, saying she does not accept or agree with the “unfathomable action” to end the testing. She says it has cost Professor Orlando about $80,000 (€50,000), which he would not confirm.

She does not have any answers as to how stable vet Bill Neilson would have sourced a draught horse’s heart but believes Phar Lap’s real heart was buried in a metal box with his other main organs on a property in Atherton, California.

Attempts to find the Phar Lap box over many decades have been unsuccessful.

Neilson had later confessed to a veterinary student that he left the ailing Phar Lap and headed to drink in a bar while the horse died. Negara suspects Neilson could have had knowledge or been part of the plot to poison Phar Lap through his gambling and drinking antics while the horse was in the US.

“One-hundred and fifty per cent – it is not Phar Lap’s heart,” she says.

Historian Geoff Armstrong, who wrote Phar Lap, Story of Australia’s Greatest Ever Racehorse, does not doubt the heart in display in the museum is that of the famous horse. But he acknowledges many elements of his death remain contested.

“I am of the fairly strong opinion that we should believe it is real,” he says. “Dr Stewart McKay was the eminent veterinary scientist of the time and I think he would have spotted a fake.”

But Armstrong says the latest developments are proof the horse still has an unrivalled place in the Australian psyche.

“All these years later we are still talking and debating and arguing about Phar Lap just proves why the horse is so important in our culture.”

Trinca said the museum had no interest in keeping secrets from the Australian public and that the mystery could be solved by testing the specimens in the future.

But, he says, as the national institution is answerable to the government, and he is answerable to a board of directors, it is crucial that any results on the Phar Lap specimen be “definitive, repeatable and independently verified”.

“The historical record is pretty clear, the theory has been tested a number of times and historians will say to you, ‘Look, there is no reason to think otherwise that this is Phar Lap’s heart, it’s been well attributed for a long time’,” he says.

“We’re interested in this, I want to know myself … but I also have a responsibility to make sure I’m not half-cocked about it.”