At the time of the First Fleet’s voyage there were some 12,000 British commercial and naval ships plying the world’s oceans. The fleet of 11 ships that made its way to Botany Bay was comparatively small given the nature of its mission. The establishment of a new penal colony on the remote coast of New Holland would provide relief for Britain’s crowded prisons and stake a strategic claim in the Pacific ahead of Britain’s rivals.

At dawn on 13 May 1787 HMS Sirius gave the signal to weigh anchor and the First Fleet embarked. The convoy consisted of two naval ships, six convict transports and three storeships to carry the food and supplies necessary for establishing a settlement. Crowded on board were some 1500 people – marines, officers, seamen, their wives, and children and at least 775 prisoners of the Crown. The departing convicts fretted over ‘the impracticability of returning home, the dread of a sickly passage, and the fearful prospect of a distant and barbarous country’ (Watkin Tench, 1789). They were unwilling participants in this colonial enterprise.

Altogether they formed a little squadron of eleven sail.

Botany Bay. ‘Sirius & convoy going in: Supply & agents division in the bay. 21 Jan 1788.’ William Bradley, watercolour from his journal ‘A Voyage to New South Wales’, 1802+. State Library of New South Wales.

At journey’s end, eight months and one week later, the successful arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay was cause for celebration. Travelling on the Supply, Governor Phillip arrived in Botany Bay on 18 January, closely followed by the rest of the Fleet which arrived over the next two days. Phillip wasted no time in judging Botany Bay an unsuitable location and on the 26 January the Fleet departed Botany Bay for Port Jackson – present-day Sydney.

At the end of the 18th century, a tiny British penal colony was established on the east coast of a vast southern continent. In their minds this was uncharted land. For the new arrivals, this was to be a self-sufficient farming settlement utilising the labour of criminals, or convicts, banished from England and Ireland. Rather than being chained and coerced, these castaways forged lively and productive communities, embracing the relative freedoms of this place ‘beyond the seas’. Far from being a prison, this was the convicts’ colony.

Slightly more than 1000 travellers came ashore and milled around at the head of a freshwater stream. Here they planted a flag, toasted their king, and looked warily into the surrounding bush.

This painting depicts the arrival of the First Fleet from an Aboriginal perspective.

This left Phillip with one remaining ship, the diminutive Supply. Dispatching her to the nearest port – Java – for help left the anxious settlement completely cut off from the outside world.

Rations were cut to half-allowance, public works were abandoned, and all efforts went towards the procurement of food until the Second Fleet arrived in June 1790, carrying provisions but also another thousand or more mouths to feed.

TENTATIVE STEPS

Scattered among rocks and trees above the foreshore were grimy clusters of canvas tents, makeshift shelters, and huts, some of which were clad in cabbage palm leaves, others in twigs and clay.

Further afield were rudimentary farming plots and gardens, along with sandstone quarries, sawpits, and shingle-cutting camps where the convicts worked every day. On the town’s southernmost outskirts was a muddy field where clay was dug for brickmaking. In coming years Sydney’s buildings would owe much to this increasingly productive brickfield.

In an effort to create order, future streets and building allotments had been pegged out while tentative plans for a hospital, jail, court, and church were taking shape. The first building to be finished was an observatory for the lieutenant

Curiously, this isolated observatory became a stopping-off point for Aboriginal people visiting the town. Initially, there had been little contact with Aboriginal people other than violent confrontations in the bush. In an attempt to learn more about them, Phillip ordered the kidnapping of several Aboriginal men in 1788 and 1789, but after a deadly smallpox epidemic swept around the harbour and beyond in early 1789, those who managed to survive kept their distance from the colony.

An unlikely turn of events in September 1790, arising from a dramatic confrontation between Governor Phillip and a large party of Aboriginal people on the beach at Manly, led to closer relations between colonists and Aboriginal locals. In what is now seen as a ritual ‘payback’ for the recent kidnapping of Aboriginal men, Phillip – to his and his soldiers’ great surprise – was speared without warning as he stood on the sand. Instead of retaliating, his men dragged the severely wounded Phillip to the safety of a longboat. Intriguingly, this non-fatal spearing ‘reset’ the relationship, with Aboriginal people coming frequently into town, getting to know convicts and trading with them.

A HARSH REALITY

As the first few months unfolded, the harsh reality of the colony’s isolation began to set in. There had been glimpses of hope and happiness, such as several marriages and the births of at least 30 children. Fertile farming soils were found at Parramatta, 15 miles (24 kilometres) upstream from Sydney. A second settlement was started on Norfolk Island.

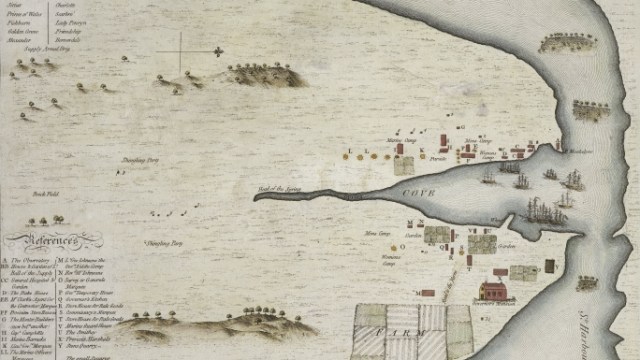

Sydney Cove. William Bradley, From ‘A Voyage to New South Wales’, 1786–1792. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

But the convicts had grown troublesome. Along with the sporadic theft of stores and belongings, and numerous runaways, the newly bonded community of cast-away strangers was rife with drunkenness, dirty deeds, and a carefree approach to sexual relations. In early January 1789, a convict was hanged for repeated acts of armed robbery. Four others earned 100 lashes each for a three-day absence from work. Around the same time, a number of convict women were cruelly punished for the theft of clothing. Similar crimes were committed by the soldiers, who faced an even harsher fate.

Elsewhere, livestock died of disease or were struck by lightning. Unfenced cattle disappeared waywardly into the bush. In some cases, though not all, through lack of skills and motivation, convicts made poor farmers while the marines, dispirited and negligent, made reluctant overseers.

RATION TIME

Two years in the making and Sydney’s food supplies were also dwindling. Still reliant on provisions shipped on the First Fleet, and with its storehouses ransacked by rats and rotten with damp, the settlement endured several periods of stringent rationing. Not surprisingly, as stored provisions vanished, local stocks of fish, fruit, marsupials, and birdlife grew increasingly scarce from rampant over-harvesting. Violent encounters with Aboriginal people became commonplace with the convicts.

‘The pot received everything we could catch or kill, and the common crow was relished here as well as the barn-door fowl is in England’.

John Hunter, 1788

Making a mercy dash to Cape Town in May 1789, the Sirius returned with little more than four months’ worth of flour. With the new year dawning and the colony’s hopes fading fast, the diarist Captain-Lieutenant Watkin Tench wrote, ‘Famine besides was approaching with gigantic strides, and gloom and dejection overspread every countenance.’

Recognising the need for desperate measures, Governor Phillip ordered a further 280 convicts and marines to sail for Norfolk Island, to bolster its farming operations and increase output. Afterwards, all things going to plan, the Sirius would continue north to China to stock up on food and supplies. The scheme was ruined, however, when the Sirius struck a reef and broke apart on the island’s rocky shore.

Painting: ‘Part of the Reef in Sydney Bay, Norfolk Island, on which the Sirius was wrecked. 19 March 1790.’ This is one of 29 watercolours made by William Bradley for his journal A Voyage to New South Wales, 1802+. State Library of NSW [Safe 1/14]

The loss of the Royal Navy escort Sirius was a huge blow to the young colony, which faced perilous food shortages and, from early 1790, pinned its hopes on the Norfolk Island settlement.

FINDING ITS FEET

By 1792 the settlement was looking more secure. The colony’s farms and gardens were starting to flourish, while recognisably English-looking cottages and soldiers’ quarters and a parade ground had replaced the uncouth scattering of tents, shanties, and bush tracks. Secure granaries and storehouses had lessened pilfering and, following a succession of crippling droughts, a series of angular rock pools – or tanks – were dug in the stream bed to divert the flow and fill with fresh water. The newly named Tank Stream kept early Sydney alive. There was still insufficient livestock to fertilise the arid coastal soil, but luckily for the settlement, corn, maize, and vegetables thrived on the alluvial lands at the head of the harbour around Parramatta.

A view of the Governor’s House at Rose-hill, in the township of Parramatta, 1798. An idyllic streetscape of carefully spaced convict cottages, each with a parcel of land for gardening or crops, frames the view of Government House at Rose Hill, soon to be renamed Parramatta. Beside the strolling woman is a set of stocks, for the public humiliation of wrongdoers and as a warning to would-be mischief-makers. Edward Dayes, after Thomas Watling. Beat Knoblauch Collection.

Closer to Sydney, convict workshops, timberyards and brick kilns produced an increasing range of building materials, tools, and domestic items. The colony’s self-sufficiency was still decades away, but the food and supply situation had improved.

As the 1790s progressed, the penal outpost – planned as a faraway prison – took on the familiar, though somewhat unintended, character of a small English town. Convicts were not locked away while still under sentence; they lived in their own freestanding cottages, among family or friends, with a private garden to be farmed in their own time. Once their sentence had been served, they received if they wished, 30 acres of land. If they were married, they received even more.

Within two or three years, soldiers too would construct and occupy their own dwellings apart from the military quarters – comfortable cottages with gardens, where they might farm for themselves or try their hand at trading or commerce.

The British government’s gamble was paying off. Here, gradually taking shape, despite the odds, was a bucolic, almost utopian, barter-based, agricultural community. Cleared, farmed, and built upon by convicts and their families, who embraced and nurtured their new homes, overseen by soldiers and guards, and ruled over by a powerful, fatherly governor.

The Centrality Of Convicts

What distinguished this colony was its dependence on convict work and, at least in the early decades, the debt it owed to convicts, ex-convicts and their families, who underpinned the colony’s social and economic wellbeing.

Shell Gangs

Initially, convict work was focused on the basics of survival and shelter: clearing land; cutting trees; forming docks, tracks, bridges, and fortifications; and gathering materials for storehouses and workshops, such as shingles, logs, saplings, rocks, mud, sand, and oyster-shell mortar. Convicts built their own houses, some in neat rows, others jumbled on the rugged shelves of The Rocks.

Convicts also hunted, fished, and collected oysters from the foreshores, as well as vegetables and tea from the bush. Historians think that this is why the population were reportedly in such good health. In addition, coming from a country where their beloved ‘commons’ had been taken from them and enclosed, they relished this new freedom to roam and forage in the bush.

By the mid-1790s, with the colony’s future looking brighter, convict labour was directed towards larger-scale agricultural production. Throughout the decade, a series of expansive government farms were established to experiment with crops, train farmers and, most importantly, bolster the government’s grain and vegetable stores.

The earliest efforts at large-scale farming took place at Farm Cove/ Wogganmagule to the east of the town. As these failed, farms were established westwards towards the Blue Mountains – firstly at Grose Farm (where Sydney University stands), then Parramatta, Toongabbie, Castle Hill, and Prospect.

These farms were often dangerous places to be, as their expansion into Aboriginal lands west of Sydney triggered frontier warfare from the 1790s through to the 1810s. Convict farmers, as both perpetrators and victims, faced mounting hostility and remained ever vulnerable to attack.

Throughout this period, an Aboriginal warrior called Pemulwuy led a large group of fighters (including escaped convicts) in a prolonged war of resistance, burning crops and attacking farms across western Sydney and the Georges River. After Pemulwuy was killed in 1801, fellow warriors and resistors waged ongoing attacks on Sydney farms. In some cases, apprehended men, such as the Aboriginal warrior Musquito, became convicts themselves.

GANGING UP

Convicts not suited to agricultural work, or who possessed useful trades and skills, worked in specialist gangs. In addition to basic public works like cutting and fetching timber, breaking rocks, and clearing bush, there were boat gangs, shell gangs, shingling gangs and a range of gangs in the lumberyard, dockyard, quarries and gardens.

After their daily stint of government work, convicts were left to fend for themselves. This meant finding private work to pay for their food, clothing, and accommodation.

Builders, carpenters, plasterers, blacksmiths, tailors, cobblers and others with specialist skills and tools of trade were typically in high demand, with many encouraged to start their own businesses. Those with servant skills found work in the homes of officers and officials. Those who could farm took on small plots of land, trading their crops at the government store for other necessities and luxuries.

TASK WORK

What made Sydney a different kind of penal experience for those under sentence was a negotiated arrangement called ‘task work’. Essentially, this involved setting minimum levels of ‘public work’ needing to be carried out for the government before a convict could undertake his or her own work, for personal gain or advancement. Free time was valuable, and in colonial Sydney it was officially viewed as an indulgence for good behaviour, to be offered or withheld, although more often regarded by convicts as a right.

Unlike their counterparts in British prisons, convicts were not confined or closely guarded. Instead, a careful balance was struck between work performed for the colony’s greater good – its roads, docks, buildings, farms etc – and free time for convicts to establish and run private businesses and ply a variety of trades and lucrative services.

While in hindsight, a radical policy of granting convicts ‘free time’ in exchange for carrying out ‘set tasks’ seems humane and generous, the rationale was far from enlightened. The flipside of free time was the lack of government provisions and the need to keep public costs down. In fact, with no accommodation to count on, and only limited food rations, convicts had no choice but to work for themselves once their task work was done just to survive. This also suited colonial authorities, who were spared their obligation to provide convicts with basic necessities.

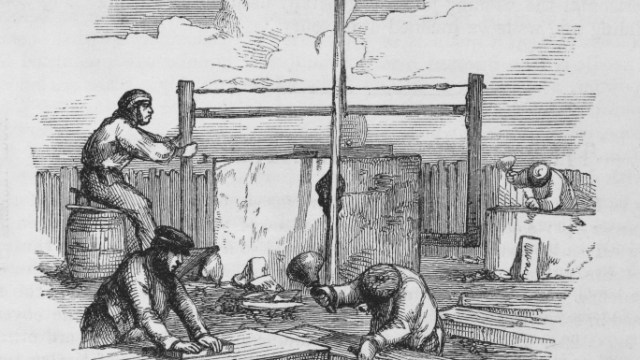

Illustration no 232: ‘The carpenter’s shop’, from ‘Illustrations of useful arts, manufactures, and trades’ by Charles Tomlinson, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, [1858]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Illustration no 195: ‘Masons at work’, from ‘Illustrations of useful arts, manufactures, and trades’ by Charles Tomlinson, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, [1858]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Despite its growing opportunities and relative freedoms, Sydney was still a place of exile, where misbehaviour and rebellion earned cruel and brutal punishments. However, the curious fit of privacy, free time and task work, together with a laxity of supervision gave the convict colony a surprisingly normal character, fostering social and economic participation and blurring the lines between free and unfree. For convicts, the impulse to bolster one’s wealth, security and comfort through trade and enterprise proved unstoppable

THE MACQUARIE’S ARRIVAL

In 1809, Major-General Lachlan Macquarie, accompanied by his wife Elizabeth, took control of the colony. In assuming command, Macquarie saw the benefits of a society where opportunities were opened to those who showed enterprise and diligence – whether convict, ex-convict, soldier or free. In contrast, what concerned him most was the dismal condition of public buildings, the neglect of public health, religion, marriage and an overwhelming rowdiness, decadence, and indifference to rules.

As the colony’s first army (rather than navy) commander, Macquarie stepped ashore with his own regiment of soldiers, the 73rd Battalion, adding force and formality to his considerable authority. Only a few years earlier, the colony had fallen under the control of a rebel administration, when the previous governor, the famed naval captain William Bligh, was dramatically deposed after he threatened the property rights of leaseholders in Sydney.

Setting to work quickly, Macquarie cancelled a long list of illegal land grants, restored civil posts, released Bligh’s allies from jail and arrested the rebel officers, ordering them to London to face charges. Little did he know that the enemies and rivals made in these early years would eventually come back to destroy him.

There were other immediate problems as well. Struggling farmers who’d lost their crops and livestock to floods and drought were now fighting plagues of caterpillars. Not only was the colony’s food supply threatened, but convicts no longer able to be fed or housed privately were being returned to government service and town, flooding into areas like The Rocks where accommodation was scarce and life was unruly.

GETTING STARTED

Commencing with an official tour of the colony, Macquarie selected level and elevated flood-free sites on the Hawkesbury-Nepean River for a series of villages – the five ‘Macquarie towns’ of Castlereagh, Pitt Town, Richmond, Wilberforce and Windsor – directing convicts into government work gangs to lay out wide, well-defined streets, create town squares and parks, and erect solid public buildings: churches, markets, courts, schools. A new turnpike road was constructed between Parramatta and Sydney, bookended with ornate tollhouses to help offset costs.

Under Macquarie, a range of social and sporting customs came under fire. New laws were passed against bare-knuckle fighting, gambling and sly grog selling. More acceptable sports, like horse-racing, cricket, and athletic tournaments, were allowed to continue at designated spots.

In Sydney, genteel parklands replaced the original bushland of the on the eastern side of the town stretching down to Woolloomooloo. Bold new edifices, like those of the three-winged convict hospital, loomed promisingly on the town’s eastern ridge, mirroring a soldiers’ barracks and military hospital on the opposing western ridge.

Undeterred by or indifferent to these new impositions, Aboriginal people continued to move freely about town. As well as trading and interacting with convicts and others, they continued to hold bloody tribal ‘payback’ contests in places like Hyde Park.

Similar kinds of indifference and interaction also occurred on the settlement fringes, with Aboriginal people a visible presence along the slowly expanding frontier. Many, however, maintained a fearsome resistance to the appropriation of their land. In the mid-1810s, faced with frontier warfare in Sydney’s Appin district in the south-west, soldiers (acting on Macquarie’s orders) conducted a brutal massacre of at least 14 Aboriginal men, women, and children.

Though this effectively ended armed Aboriginal resistance in Sydney, a similar story of violent dispossession unfolded across the state in the following decades, as convicts formed the vanguard of colonial expansion into the tribal lands of more Aboriginal groups.

BUSH TRACKS TO BOULEVARDS

Police constables and soldiers, patrolling newly defined curfew areas, strode along freshly paved footpaths, while town squares were prettified with monuments and masonry. Streets were renamed and re-levelled, while formerly roving pigs, poultry and goats were banned from view behind lofty walls and fences. Out on the fringes, stylish villas, and neat cottages in soon-to-be fashionable zones to the south and east snubbed the ‘untamed’ enclaves of The Rocks and Cockle Bay, where the far-from-gentrified convicts and ex-convicts lived, loved, and socialised.

Further afield, horizons were expanding. Having just extended its footprint beyond the once impassable Blue Mountains and bristling with commerce and shipping – whale oil, cedar, seal skins and sandalwood – the garrison outpost of Sydney was eager to shed its penal past. Many others, particularly Macquarie’s superiors in London, worried that the colony was growing up too fast, ‘taking on a character more colonial than should belong to a gaol’.

Macquarie arrived in Sydney in 1809 and, much to his surprise, found a seaport thronging with activity and optimism. This two-part view of Sydney Cove captured from the rocky shores of Bennelong Point (where the Sydney Opera House now stands) shows the waters crowded with trading ships, skiffs, tenders and Indigenous canoes. On the right is the two-storey Government House amid picturesque grounds and mature trees, with the Governor’s finger wharf jutting into the cove. On the skyline beyond are the long dormitory blocks of the soldiers’ barracks where York Street now runs. Beside this is the squat St Phillip’s church and its medieval turret, which held the colony’s first town clock. Further to the right are the battlements of Fort Phillip and a pair of lofty windmills crowning the ridgeline. Below are clusters of huts and cottages sprawling towards the waterline, where trading houses, handsome villas, shipyards and docks give Sydney Cove a European character.

By 1815, Macquarie’s Sydney was a thriving port town, fed by large, productive farms on the Cumberland Plain, with expanding local industries, employing an ever-growing population of current and ex-convict colonists – most of whom now called the place home. Following years of declining convict arrivals, a laxity in supervision, along with wide-ranging incentives and opportunities to prosper, a growing commercial self-confidence, spurred by the unlocking of farming lands to the west, had given the colony hope. Blessed with good health and an agreeable climate, townsfolk saw the regular arrival of newborn babies as cause for celebration. In Lord Bathurst’s words, the colony might become ‘at no distant period a valuable possession of the crown’.

For the new governor, however, progress boiled down to building and infrastructure. In his mind, bold and expensive plans for a self-confident city were taking shape. Town squares and boulevards would soon replace the old bush tracks.

Footnotes

1.John Hunter, An historical journal of the transactions of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, John Shopdale, London, 1793, p70.

2.Watkin Tench, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson in New South Wales including an accurate description of the situation of the colony; of the natives; and of its natural productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, Chapter 5, ‘Transactions of the colony, from the beginning of the year 1790 until the end of May following’. See: http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/p00044.pdf